©2021 Mark Seth Lender, All Rights Reserved

The camera is my notebook. In my fieldwork with wildlife a still camera is the one indispensable tool. Nothing can replace it. What I see with the naked eye is important but it is only a fraction of what lens and camera and photograph divulge. In the vast majority of wild animals reaction times are faster, their senses more refined, their responses subtle as compared to our own. The still camera slows things down to a level that suits human perception. Relationships between different species, interactions each with their own kind, what transpires when living creatures appear to be doing nothing at all – in all these circumstances high-resolution still photography at high frame rates is critical. Why not film or video? For the very same reason eye witness accounts are known to be so completely unreliable. Even slow-motion will not do. Regardless of speed, the eye is led by the action and cannot linger. In contrast, studying the changes frame by succeeding frame, closely, in fine detail, selecting what to ignore and what to keep becomes an intimate exploration. Telling sequences emerge. These have opened a window for me on what animals think and what they feel and above all their fundamental and profound similarity to us. Image and written word are therefore intimately connected in my work.

If I describe the following scene: “A sailor bends a nurse in her white uniform back on his arm and kisses her,” a single image comes to mind. We know that the man and the woman are complete strangers, the place particular, the moment exuberant and we know the reason why. Alfred Eisenstadt took that photograph in Times Square more than seventy-five years ago. Yet there is hardly a person who does not know it. Even those born long after the photographer himself was gone. Cartier-Bresson said what photos like this capture is, The Decisive Moment. I owe him a great deal. The Decisive Moment is the progenitor of the work I am doing now. For years I tried to create its equivalent in my photographs of wild animals. The images at their best were compelling. But not decisive. Finally, I realized the concept is valid only when we are speaking of human beings. Not because of some spectacular quality we possess. Rather, out of our ignorance. The only creature we know sufficiently well to find the moment that is decisive is ourselves. We know how we behave, what our behavior means, sometimes even so far as to the place and the time from a single photograph. In other words we know the context. We know it intimately. Every attitude and gesture. We are drawn to us because we know us.

Beauty, the ineffable beauty of the Natural World also attracts and compels and leads to the presumption that here too, we know; and therefore go on to assume that any beautiful image is iconic. Not so. Not even when it comes to landscape. Monet painted his famous haystacks at similar times of day in subtly changing light at least thirty times. He complained of the near impossibility of the task. One haystack however beautiful does not tell us nearly enough. We need to see – held up in front of us – what went before and during and what came after.

With Nature as a whole and wild animals in particular, presentation of a single frame cannot convey the story but in fact misleads despite the photographer’s honest intent. Acquisition of a large volume of sequential raw images is a challenge but finally, a matter of technique. Cooking the raw is the Magic. It is the only way I know to grasp the totality, to see the Natural World as its wild inhabitants see it. I call the result The Decisive Sequence.

When it comes to living things the final product of this bricolage is Inclusion. Logic, reason and doubt; love and fear and loyalty; reprimand, apology and acceptance, it is all there and all in plain sight.

Eyes make the Face. We are the Animals with Faces. Paper wasps to blue whales. Together we are outweighed by diatoms, vastly outnumbered by nematoid worms. Eyes have been here at most one eighth of the time life has been on earth, us only for an eyeblink. And we are very much alike if for no other reason than behind these many different forms and formulations of eyes and faces is where consciousness for all Kind resides. Too much time and ink has been spent on the differences. Animals look us in the eye. We look them in the eye. What is that if not recognition?

We are Them, they are Us. If they cease to exist, we cease to be Human.

*

* * *

*

Pas de DeuxThe takeoff of this mated pair of sandhill cranes is pure form. No one frame conveys the shape nor the extent. Bodies in tense preparation, the first springing step from the icebound pond to the last when gravity is broken, we have to see them all. Wings up. Wings down. The thrust of a foot splashing through ice and the rebound captured in a separate moment. It is Tallchief and Nureyev, Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, Baryshnikov and Kirkland.

Beauty, the ineffable beauty of wild things is what draws us to Nature. Not as a mere aesthetic but an inexorable, irresistible longing, one that derives out of recognition. In the Natural World the beauty we perceive is its likeness to ourselves. It is not the color of sunrise or sunset but its resonance, somewhere deep inside us. We are part of it, it is part of us, as vital to our being as air and water and blood. Take that from us, we are diminished from close and present to the vanishing point. The dungeon is a cruel punishment not only for its isolation but because it has no windows. Dehumanization can also be achieved when the windows are there but there is nothing outside to see. The end of the Natural World will be a solitary confinement without end. And you must prevent it. You must.

“I believe in beauty. I believe in stones and water, air and soil, people and their future and their fate.” – Ansel Adams

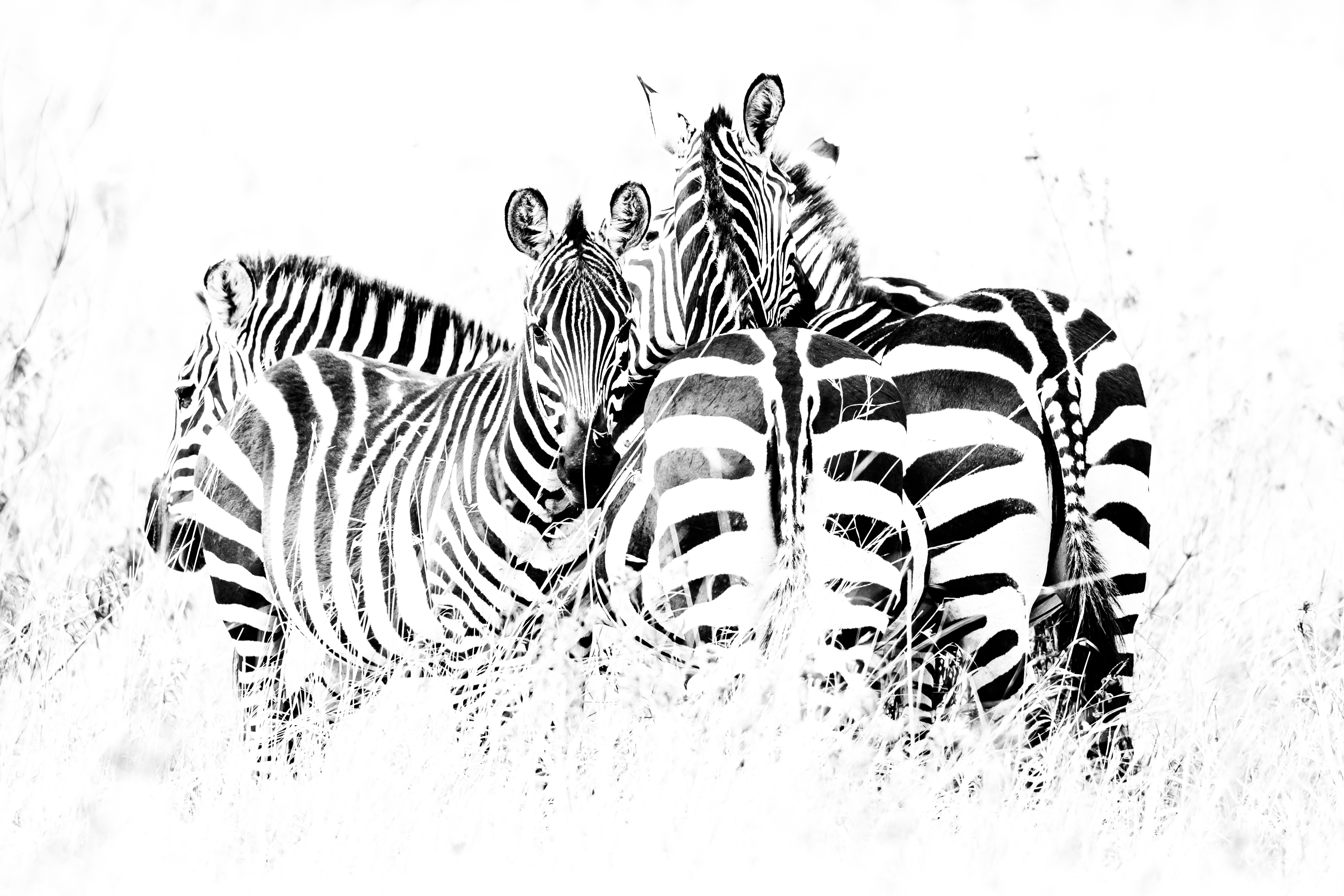

Why do zebra make themselves so abruptly, completely apparent? It was recently proposed that biting insects are dissuaded by stripes. If true then incidental. What zebra fear is not being nibbled but being eaten, whole. Stripes are the solution to that larger risk. However, their function cannot be understood in the person of a single zebra much less a single frame.

Zebra stripes work in the contiguous presence of many zebra. More particularly many zebra in motion. As the photographs of this Horse of a Different Color demonstrate, even in a small group it is difficult to see where one animal stops and the other begins, how many there are, the direction of movement. The confusion marvelously extends to which end is the head end and which end is the rear end of any individual. Proof is in the mechanics of attack. Lions do not attack the herd. They do not throw themselves into the midst. One animal alone becomes the lion’s singular focus and once that focus is achieved – if it can be achieved – a lion will not allow concentration to be broken by changing targets or trajectory, there is neither time nor energy for that. Therefore, what zebra earn in stripes is herd immunity of the literal kind.

During WWI, ships were painted in broad and irregular zig-zag patterns called Razzle Dazzle which made it hard to impossible for U Boats in particular to gauge range, speed, even the direction of travel in distant targets. It was Winston Churchill who first promoted Razzle Dazzle, an idea brought to him by the biologist John Graham Kerr who in turn relied on studies of disruptive camouflage in animals, particularly… the zebra.

“A magician makes the visible invisible. A mime makes the invisible visible.” – Marcel Marceau

There is the length of the beak, its heft, that it comes to a point. The two siblings going at it look like they want to kill each other. Certainly they could. But as the frames unfold what becomes clear despite the armament or rather because of it, is that the entire interaction is remarkably constrained. Strike after strike these young great blue herons meticulously avoid each other’s eyes. No blood is drawn. Except for the limited contact of their stagey sword play they do not even touch each other. There is a seesaw quality to it. Which might imply they are evenly matched, that perhaps this is the reason for restraint. Not true. Of the two siblings in conflict the one to your right is actually bigger and therefore a few days older, and fully plumaged. The other, with slightly less mass and a shorter reach, is nest-bound. What they are doing is taking turns. As if the encounter was transcribed in Labanotation and the whole a choreography.

There are in total five birds on the nest. A third sibling, younger still and smaller, does not participate but pays attention. The bird behind and to the left is the mother. She is the cause of the conflict or rather, what she carries is the cause: Food. All at once all her children remember and turn their attention, toward her…

“For the love and the tenderness of a mother for her child is not consequent upon reason, but upon the activity of the imaginative faculty, which is found in most animals just as it is found in man.” – Maimonedes, The Guide of the Perplexed

Polar Bear was sprawled, flat out, face down, arms at full length by her sides and her paws facing up, as if she tripped and fell and made no attempt to break the fall – as much bulging belly in contact with the ice as possible. It was apparent from more than a kilometer away that one of those seal/bear convergences had recently occurred, the consequences of which were fully in evidence: over fed, over heated, over slept, Polar Bear.

Our ship and the uninterrupted white between her and us was met with awareness but indifference. A form of iceberg? Seen before? Polar Bear yawned, eyes closed. But as we neared, dead slow in deference not only to the bear but to the pack ice, the small contingent of people at the deck rail must have come into focus. Polar Bear blinked, rolled over, stared for a long moment and, then came slowly towards us. By the lack of a neck ruff, the shape of head and jaw, the absence of that telltale shag of heavy fur along the forelimbs, it became apparent that Polar Bear was a she. Finally amidships, she rose on her hind legs all the way to her full height (which I gauge to have been eight feet) and just stood there. She made eye contact with every single person making eye contact with her.

In the portrait shots in this sequence Polar Bear is directly below me, no more than four meters from the front of the lens. What you see in her face is not threat and certainly not hunger but a question.

“What Kind of Bear are You?”

We were the first human beings Polar Bear had ever seen, of this I have no doubt. Why she chose me in particular to come to, to connect with like that and for such a long time I cannot say; the wonder and the connection were mutual. I have been privileged to interact to one degree or another with perhaps a hundred of her kind over the years. Polar Bear is and will likely remain my favorite of all time. She is the one who changed me.

“Nanuq is smarter than you” – A saying of the Inuit Elders (told to me more than once)

Before dawn, osprey cruise the near shore of Long Island Sound. On a good day there is no wind. The surface is flat. Even in the half-light the hunting is good. This would be reason enough but there are hatchlings on the nest, hungry all the time and the working day for an osprey in this vital season needs to be as long as possible with the earliest possible start. Regardless of the weather. On the waterside porch that stands above like the bow of ship I went out to wait for them in the dark. I knew what I was after, osprey at eye level, at that singular point just after the plunge and grasp and a fish in their talons, rising, shaking off water, the eyes of bird and fish glinting the droplets flying handfuls of precious stones thrown into the sky.

The morning did not disappoint. A young male osprey did exactly what I hoped he would do.

Everything about these photographs has a dual quality. They are strange because, how often do we have a view like this of a bird of prey. The normally distant, so sharp and clear and close. That last, deliberate look directly into my eyes and yours, held there, suspended. All this is uncommon. The headshake? That is the familiar. A dog comes running from the waves spinning his head and soaking everything in all directions, including you if you do not have the good sense to get yourself out of range. It is a commonplace. And here is Osprey, this feathered dinosaur and his hundred-and-fifty-million-year-old self performing the same act in the very same way as Canis familiaris?

“The question is not what you look at, but what you see.” ― Henry David Thoreau

It was enough, more than enough to have captured in such a complete and perfect way that osprey shirring water, and this when there was hardly any light. Provoked by these images as strong in the mind’s eye as in the camera, I already knew what I would write, even the title. It had been a great morning.

The camera is work. It puts distance between you and what you see. It blunts direct experience. To make up for that as I often do I stood looking toward the horizon, taking a moment for myself before hefting the tripod onto my shoulder. It was just after five in the morning on the fifth of June, in the quarter hour glow before the sun divides the horizon line into left and right. And I heard the splash. And turned. And there they were: Three white-tailed deer splunging and crashing down the tideline.

They had made a mistake. Not the salt water (they can swim for miles if they have to) but that there was nowhere to go. And they knew it. The buck in the lead was inexperienced. The doe who was older and her fawn of the previous year, no doubt by another father, were following him because follow the leader is what they do. The doe was pregnant, probably by that buck and maybe that had something to do with it. Except, every time they stopped and they stopped often, all three – the doe, her yearling, the buck – would each look in a different direction. This way… that way… Turn… And look…. And turn…. And look… Every time the buck moved on the others held back (just the slightest hesitation), the further signature of their doubt. It was too remarkable. I could not absorb it. Though I was riven to the spot you see them now better than I could. In the photos you can read their minds.

“All that exists lives. The lamps walk around, the walls of the house have voices of their own. Even the chamber-vessel has a separate land and house.” – Chukchi shaman (1900) [Copied from the Cross-Continent Exhibit at the Museum of Natural History by the American abstract painter, Edwin Ruda]

Walrus was on his way to rejoin the herd. Then he noticed me. He turned, went back into the fjord and as soon as he found his buoyancy swam towards me, at remarkable speed, just off the shoreline. Male Atlantic walrus are very large. Something appreciated best at a less than safe distance. Twelve meters is well beyond the parameters of safe, and that is where he ended up.

I froze. And made ready to leave my camera gear and run.

Look at the posture. Look at the eyes. Notice the questioning uncertainty as he approaches, how “What’s this?” becomes “WHO THE HELL ARE YOU!!” (double exclamation point, one for each tusk) then, “Well, all right, you’re not much” then “I don’t know…” then “WHAT? WHAT? WHAT’S THIS!” and finally, “OK. But stay put. Because, I’ve got my eye on you.”

The most important thing in the presence of any wild animal is listen to what they have to say. I listen with my eyes, attuned to body language, where the gaze rests, whether wrinkles around the eyelids are relaxed or tense, the eye wide open or not. My ears are least and last because aural cues in these encounters are few and far between. Long before the prairie rattlesnake rattles, she expresses herself by the way she is coiled, the angle of her head, even what her tongue is doing. This is how she tells you what she thinks of you; your being where you are; how much you are pushing your luck.

When the grizzly bear roars it is far too late.

Conversely, when an elephant wants to reach out to you it is not by word or elephant voice but a silent, older and more nuanced form of talk and if you are lucky, really lucky, the outreach of a trunk.

Great or small, wild animals assume you are just like them and that you will understand everything they have to say.

“And only those few of us unskinned of fur,

unstripped of bone, unplucked of feather

respected in our quills, scales, horns, tusks

and whatever else some of us may have

of ingenious albumen,

we are – great lord and master – your dream,

which absolves you for a brief moment."

- Tarsier, Wislawa Szymborska

Gyrfalcon! I ran out and began to shoot. Middle of a blizzard. Minus 4 Celsius and blowing thirty knots, my fingers immediately numb. Not that I noticed. I had never seen a gyrfalcon and through the white-paint washout of snow there was only the noun and the naming and not the particulars. Then he was gone.

Moments later Gyrfalcon came back. The snow had stopped though not the wind and though it was much too cold to stand there he was so close and so clear I stayed, taking photograph after photograph after photograph.

What I try to capture is transition. The subject in greater or lesser proximity (spatial or psychological) with its own kind or other species with whom it interacts; movement great or small; general aspect including when the body is tense and when it relaxes and the back and forth between these two states; above all the eyes and where they are look and in particular when they are looking at me. Theirs is an empirical process. Rapid and precise. Sometimes I have a sense of things but there is never time nor concentration in the instant to note the details nor to interpret, to any depth, what they mean. I did see the blood on the gyrfalcon’s feathers. I assumed he had just made a kill. It was not until late that night when all the photographs were off the camera and onto my screen and both the technical demands and the excitement were behind me that I realized the blood was his own.

Hawks, falcons, owls especially but in essence any bird that flies has greater visual acuity than Homo sapiens. Even the four-legged species who see no better than us are more attuned, both to the world around them and to each other. They process information more quickly. React faster. If you don’t believe me try to sneak up on a northern cardinal, a moose, a common gray squirrel, an African lion even in the near-dark.

Which is to say, Gyrfalcon saw it coming and at a distance. And yet could not escape.

At this latitude, there is only one creature I can think of who could have hurt him like that. Snowy owls were present and they are big enough but I don’t think they are fast enough. Another gyrfalcon except they are not generally aggressive and I found no reports of one trying to kill another one. This leaves only peregrines. In early November when these photographs were taken, peregrine falcons should have been well south of Churchill Point. They can’t take the Arctic winter. But the Arctic is now too warm. Even in Greenland and for some years now, the peregrines have been driving north and for the first time there is conflict between them and gyrfalcons. In the past, according to what I’ve been told, despite close proximity conflict did not exist. These photos are probably the first evidence, circumstantial though it may be, that a climate war among falcons who for thousands of years had left each other alone, has come to Hudson Bay.

“We patronize the animals for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate of having taken form so far below ourselves. And therein we err, and greatly err. For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours, they are more finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other Nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.” ― Henry Beston

When a pride of African lions heads out to hunt it is preferentially a cooperative venture. A lion alone is less successful and at much greater risk of harm. Cheetah can go either way. With equal success they work collectively or hunt alone though both styles require intelligent preparation.

The part of the Maasai Mara where this sequence was captured is particularly flat except for the termite mounds. They provide the only vantage that clears the tall grass where the hunted hide. I know female cheetahs mark termite mounds with their urine because in this sequence if you look closely, you can see that happening right in front of you. Both the boundaries and the critical elements of a territory are marked. Marking means worthy of possession. It means mine. Termite mounds are well worth owning.

Sitting at the highpoint Cheetah surveys her domain. She covers the entire field of view from the only place that allows her to do so. Each point within her purview holds her gaze. It is not a casual glance. It is a process of consideration. Yet there is no tension, look how relaxed her body is. Based on what she has seen and recorded and in counsel only with herself, Cheetah works out her plan. Strategy in mind she descends and stretches and disappears into the night…

Just as much of my work is before sunrise, a good part of it takes place after sunset. Close to the equator the sun comes down like a portcullis door. It is light and bright and a moment later dark. In the witchy hour between the gray and the absolute black is where I want to be. That is my strategy. In the half-light the camera sees everything.

“Man has nothing that the animals have not at least a vestige of, the animals have nothing that man does not in some degree share.” – Ernest Seton Thompson

The Day of Perfect Sight

The Angel Lucre strides across the Earth, his gold wings and gold robes, too bright for mortal human beings to look upon. He holds a black sword. It glows, sputters like a candle and drips a black oily fire and the smoke of it makes the air impossible to breathe. Where his foot falls, the water turns foul and impossible to drink. Life cannot live in his shadow nor in his light. Abroad among us he knows no bounds or borders and strides the seven continents at will. No red mark, painted on the lintel of your house will prevent him. All magics fail. There will be plagues:

Darkness

Locusts

Flood

Drought

A Plague Upon Amphibious Creatures, and Those That Only Swim, and Those That Only Walk on Solid Ground.

A Plague upon the Creatures of the Air.

A Plague of Fever.

A Plague of the First Born, who are now The Old among us.

We remain in Slavery. We cannot see the horizon…

A flock of birds passes over, Great Egrets, the first of their tribe. Sure in their flight they level the eye. Now a single osprey comes, sailing against the curling breeze down the shoreline towards the sun. The osprey is a month late. Great Egrets a month early. No matter. They are here. There is a pair of Grebes diving and fishing above the sandbar and cruising behind, Crested Mergansers, the white disk of the drake’s head markings; I’ve seen both of them many times but never in this close stretch of water. I recall, this morning I heard an Oyster Catcher. And yesterday there were Glossy Ibis, only a handful. But look! Now! On this day, different from all other days and nights, the entirety, the whole migration, Ibis in a long line cleaving dark and low, their wings flashing and the waves roiling just beneath. They lift and circle and break apart above the barrier island, sputtering like leaves among the island’s leafless trees where they will nest and breed and lay down their precious cargo. A flock of Snowies, white plumage adorned for the season and its intent, rise in greeting. In the near woods the Great Blue Heron sits and waits.

The manacles are rusted and have no locks. One kick would be enough to break the chains.

Lucre the Angel in his golden aspect roams, even the lands of ice and the lands without rain. Next year or the year after we will banish him, the Angel and his Minions. Forever from our oceans and our cities and our mountains and our plains we will bid them, Depart. Once like the child Moses we were drawn to shiny things but our hand was stayed; and though we took instead the burning ember and touched our lips and were burned, we are not destroyed. We are still here. The Earth will have its Day. And your children, and your children’s children will be led out of slavery where we were captive to the brilliant that was an empty meal, with no savor and no meaning.

And they will live and you will live to see it.